The working life of French-born Jacques Barzun (1907-2012) spanned the best part of three score years and ten from the 1930s into the new millennium. He is probably the premier writer on education and cultural studies in the 20th century and it is a telling commentary on our intellectual life that he is practically unknown in Australia, like Rene Wellek (literature), Karl Buhler (psychology and linguistics), Ludwig von Mises (economics) and Ian D Suttie (psychoanalysis).

Barzun combined the roles of scholar, author, teacher and university administrator and the bulk of his output is remarkable considering his family, teaching and administrative responsibilities. He wrote, edited or translated over 40 books and countless chapters, introductions, forewords, academic articles and pieces of high journalism for the educated public. This piece was written for free enterprise policy analysts to alert them to the need to pay attention to the cultural agenda where the left captured the high ground in the march through the institutions of the west.

We now realise that something has gone wrong on the left and there is a need to reactivate the triple alliance of social democrats, cultural conservatives and classical liberals who fought on the culture front on the Cold War. Barzun’s work provides a background for the work of this alliance with a running commentary on the cultural life of the United States from the 1930s to the year 2003 when his last book was published.

This article introduces Barzun and his career, starting with his work on race and moving on to the culture of democracy and issues in education and cultural studies.

Jacques Barzun (1907-2012) is probably not a household name these days, especially among economists and policy analysts because he did most of his work decades ago in education, the history of ideas and cultural studies. However in light of the importance of a robust and vibrant cultural/moral framework among the pillars of classical liberalism Barzun’s historical and cultural commentary stands as substantial contribution to the liberal cause. This matter has become urgent because classical liberalism is strong on philosophy and economics but has been blindsided on the cultural front.

We do not live by bread and technology alone because our lives gain meaning and purpose from the myths and traditions which constitute our non-material heritage. Our daily transactions are dignified and lubricated by civility and good manners. Both the higher and lower orders of the fragile structure of civilization are sustained by institutions such as the family and the universities. These institutions are under threat from various doctrines and schools of thought which are also part of our cultural and intellectual heritage. If we lose the capacity to subject our heritage to imaginative criticism we run the risk that the bad will drive out the good. It often seems that this process is well advanced and it is important to understand how it has happened in order to reverse the trend. Barzun’s work sheds a deal of light on what went wrong.

Economic liberals may appear to have little interest in spiritual and cultural matters but this is not entirely true and the impression arises for three reasons. First, it is not possible to talk usefully about every social problem at once and economists tend to talk most about the things they know best. Second, we do not speak with one voice on such matters. Third, we do not usually see these things as part of the agenda of state policy. We do not aim to impose religious or cultural values, instead we wish to sustain a type of order in where others are allowed to pursue different ends, even on fundamental issues, as Hayek proposed (Hayek 1960, 402). That order is under serious threat in part due to excessive tolerance of radical activists especially since the 1960s. The great historian of ideas Arthur Lovejoy was the prime mover in setting up the American Association of University Professors in 1915 to promote academic freedom. During the Cold War he argued from the premise of protecting academic freedom to conclude that members of the Communist Party of America should not be appointed to teach in the universities (Lovejoy 1948).

Barzun‘s working life spanned the best part of three score years and ten from the 1930s to the turn of the millennium. He was probably best known for his writing on education until Dawn to Decadence (2000) showcased the remarkable breadth and depth of his scholarship. The sheer bulk of Barzun's output is remarkable considering his teaching and administrative responsibilities. He wrote, edited or translated over 40 books plus countless chapters, introductions, forewords, academic articles and pieces of high journalism for the educated public. A comprehensive bibliography including his early work under pseudonyms would be a major work in itself.

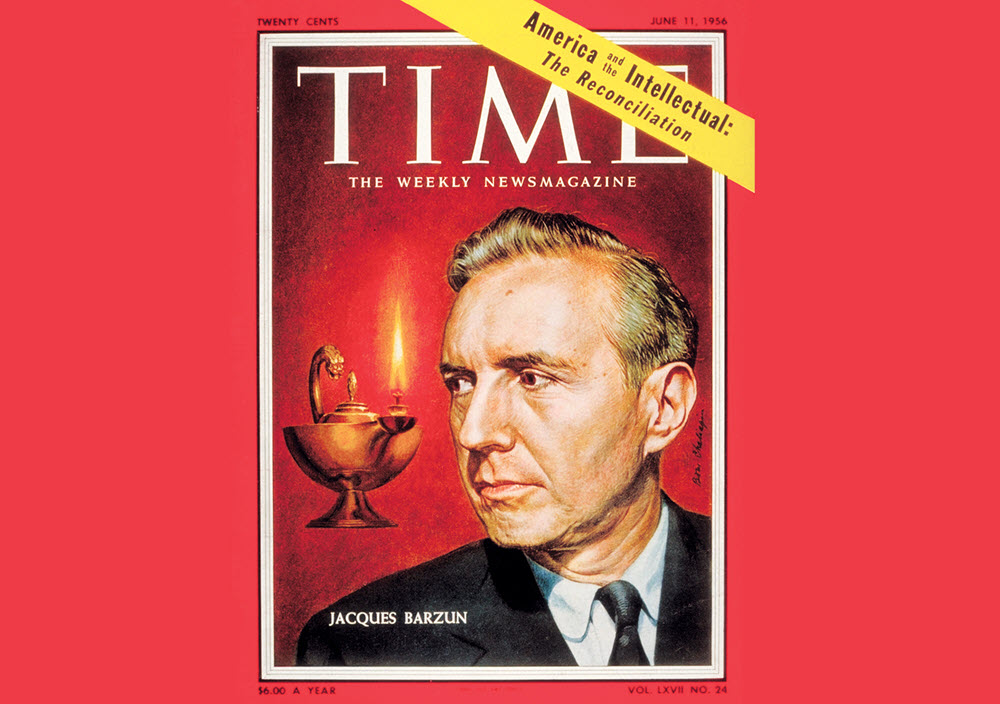

He fought a long battle against what he called hokum, ideas with no basis which achieve credibility by repetition. One of these is the description of the 1800s as the century of laissez faire. He pointed out that the era of laissez faire in Britain was probably as short as a decade, from the repeal of the tariffs on imported grain (the Corn Laws) to the introduction of the Factory Acts and similar regulations. His reputation achieved a boost late in life when his massive and scholarly book Dawn to Decadence (born of longevity and insomnia as he put it) appeared in the year 2000 and quickly became a surprising best-seller. This was not entirely a new experience for Barzun because he was touched by the fickle flame of celebrity in 1956 when he featured on the cover of Time magazine.

In the Author’s Note Barzun advised that he set out to be “selective and critical rather than neutral and encyclopedic”. Those who have tried to read this wrist-breaking 900 page tome in bed will be pleased that he did not set out to be more informative and that the scope of the work was only the last 500 years. A review essay by Roger Kimball conveys a sense of the richness and density of the work (Kimball 2000). Asked about the origins of this remarkable achievement and the reason why it came so far behind the main body of his writing, he explained:

When I was just beginning to teach, about 1935, I thought I would write a history of European culture from 1789 to the present. I was dissuaded from it by a friend of my father's who was the director of the Bibliotheque Nationale. I was doing research there and he asked me what I was doing, and I told him, and he said, ‘Oh, young man, please don't do any such thing. You'll write about things that you know at first hand, and you will fill the rest out with things you get out of secondary texts. There's no need of that at any time.’ So I said, ‘How long should I study original works before I start writing?’ He said, ‘Well, why don't you wait until you are 80.’ I think I waited until I was 84, 85. (Gathman 2000)

The Man

Barzun’s feel for the roots of twentieth century culture can be traced to his childhood in Paris where his parents conducted a modernist salon. His father worked in the Ministry of Labour but his heart was elsewhere. He wrote novels and poetry and hosted the likes of Guillaume Apollonaire who taught Jacques how to tell the time on his watch and Marie Laurencein who painted his portrait. Other regular visitors included the painters Marcel Duchamp and Albert Gleizes (a founder of cubism), the innovative composer Edgard Varese and foreigners such Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington and Stefan Zweig. Members of the older generation such as Andre Gide appeared occasionally to find out what the youngsters were up to.

During the war his father was called from the trenches for diplomatic missions and after a journey to America he offered Jacques the opportunity to complete his studies at Oxford, Cambridge or a leading American college. The young Barzun was reading James Fenimore Cooper and other books about the red Indians so he opted for New York. He arrived young enough to become well embedded in the popular culture and later he wrote “Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball, the rules and realities of the game – and do it by watching first some high school or small town games” (Barzun 1954, 159). In 1923 he entered Columbia College where among other activities he was president of the literary and debating clubs and drama critic for the Columbia Daily Spectator. He graduated at the top of his class and lectured at Columbia University where he became a full professor in 1945, Dean of the Graduate Faculties in 1955 and the inaugural Dean of Faculties and Provost of the University in 1958. This level of involvement in administration by a serious teacher and scholar has few parallels and it adds authority to his account of the travails of the universities. In 1967 he resigned from his administrative duties to focus on teaching and writing until he retired in 1975. He continued writing, lecturing and working in various posts including Literary Advisor to Scribeners and a directorship of the Peabody Institute for Music and Art at Baltimore.

He started teaching as an undergraduate, privately tutoring students of French. Two of his middle-aged pupils did so well that the head of the department in a major university invited Barzun to a meeting. He laughed aloud when confronted with a seventeen year old who he had contemplated offering an instructorship. As a postgraduate student he formed a small commercial venture with some colleagues "a perfectly legal and honest tutoring mill, whose grist managed to renew itself as we managed to put the backward rich through the entrance exams of famous colleges not our own" (Barzun 1981, 21). During that period he also wrote detective stories and book reviews under a pseudonym. One of the books which he reviewed was Whitehead's Science and the Modern World. This convinced him that there was no essential tension between the "two cultures" and ever after he envisaged science and the arts as harmonious joint tenants in the house of intellect.

Some of his early university teaching experiences were tinged with melodrama.

A big bruiser of a student whom I had failed came to my office threatening bodily harm, then hounded me by phone, wire and letter, pleading that I should pass him ‘in the name of Christian brotherhood’ for he had ‘powerful friends in Brooklyn’. Nothing happened, but two years later, the tide turned in my favour. Another student, an impressive-looking middle-aged man in an Extension course, made a point of showing his gratitude, first by inviting me to his Turkish restaurant and then intimating that if I had any enemies he would only be too glad to get rid of them for me gratis. (ibid 34-35)

In the 1930s he worked with Lionel Trilling when they shared a famous course on Great Books at Columbia. They became warm friends and Barzun was close to the heart of the progressive intellectual culture of New York, though unlike Trilling and his friends he was never a man of the left. A reporter from the Austin Chronicle took this up in an interview after the launch of Dawn to Decadence. He replied “I had no Marxist colouring, such as they had...I stood aloof, although not hostile, and I take it they weren't hostile to me. They deplored my blindness.” (Gathman 2000)

Race and the Culture of Democracy

Barzun’s doctoral dissertation focussed on class and race in pre-revolutionary France (Barzun 1932). His second book on the same theme, Race, A Study in Modern Superstition appeared in 1937 although it was not planned to be a tract for the times because the work started before the rise of Hitler. Barzun charted the protracted dispute in France over the “race” of the nobility versus the bourgeoisie which was one of the divisive factors which contributed to the French Revolution. He suggested that “race-thinking” persisted after the Revolution as a component of the struggles between nations, political parties, religious faiths and social groups. For Barzun “race-thinking” is one of the ways to justify collective hostility and it is most dangerous and powerful when it operates in partnership with other motives such as the nationalism of the Nazis, the socialism of the communists and nowadays the radicalism of Black Lives Matter. “Marxist doctrine at its purest is in form and effect racist thought. Indeed the class struggle is but the old race antagonism of French nobles and commoners write large and made ruthless. Marx’s bourgeois is not a human being with individual traits but a social abstraction, a creature devoid of virtue or free will and without the right to live.” (Barzun 1965, xi)

By 1937 the issue of race had become more than an interesting topic for a doctoral dissertation. The book was reprinted in 1965 and the Preface “Racism Today” makes interesting reading half a century later. He wrote “As long as people permit themselves to think of human groups without the vivid sense that groups consist of individuals and that individuals display the full range of human differences, the tendency which twenty-eight years ago I named ‘race-thinking’ will persist.” (ibid, ix) Individuals should be treated according to their personal characteristics such as their fitness and qualifications for particular tasks but as long as the qualities required for the tasks are not race-related there is no need to make race an issue. If it is made an issue then “race-thinking” will continue to generate muddled thinking and inappropriate actions with potentially dangerous unintended consequences. He insisted that giving up race-thinking means equal opportunity but not affirmative action. Because there are no positive or negative traits that are race-related it follows that “sentimental or indignant reversals of the racist proposition are false and dangerous. The victims of oppression do not turn into angels by being emancipated… Race-thinking is bad thinking and that is all.” (ibid, xiv)

On the topic of affirmative action he wrote “When injustice is redressed, the hitherto outcast and maligned group must not benefit in reverse from the racism they justly complained of. They do not suddenly possess, as a group, the virtues they were previously denied, and it is no sign of wisdom in the former oppressors to affect a contrite preference for those they once abused.” (ibid, xv) He recalled a report from a Fullbright scholar in Paris who witnessed a memorable celebration in the Latin Quarter. A contingent of white writers and artists led by Negro writers and accompanied by French and American students had ceremonially burned the white race in effigy! He regarded that as an emblem of suicide by both parties because inverting the racial hierarchy leaves race-thinking intact and probably even stronger than before because it is sanctified by the self-righteous sense of correcting a great injustice.

Barzun went on to address the situation when a representative of a group is depicted in a work of art or literature in a way that some people find offensive. He instanced the repeated attempts to have The Merchant of Venice banned and Huckleberry Finn removed from library shelves. Nowadays he would be referring to the removal of statues of Confederate soldiers and politicians. “This anxious wrangling which goes on about books and plays seems at times trivial but it is in fact fundamental. If democratic culture yields on this point no prospect lies ahead but that of increased animosity among pressure groups… In social and cultural relations the law rarely intervenes effectively; the protection of rights and feelings only comes from decency and self-restraint.” (ibid, xvi my italics)

The secularisation of Christian moral fervor

In a wide-raging commentary on American civilization in God’s Country and Mine (1954) Barzun commented on the mounting impatience of social reformers and he posed the question “We may ask when and where the world has seen a whole nation developing the habit, the tendency, of continually looking out for those who in one way or another are left out…Yet look at the subjects of unceasing agitation in our daily press: the rights of labour in bargaining, the fight for fair employment practices, for socialized medicine, against discrimination in Army and Navy, in colleges and hospitals, in restaurants and places of public entertainment; in a word, the abolition of irrational privilege”. (Barzun 1954, 12-13). He had encountered one of the consequences of the phenomenon which Paul Craig Roberts later described as a “land mine” at the very basis of Western thought. “The 18th century Enlightenment had two results that combined to produce a destructive formula. On the one hand, Christian moral fervor was secularised, which produced demands for the moral perfectibility of society. On the other hand, modern science called into question the reality of moral motives.” (Roberts 1991). These tendencies might appear to be contradictory but they have not balanced each other. The first drives demands for the immediate and comprehensive rectification of all the forms of injustice and inequality which are attributed to our traditional mores and the institutions of democratic capitalism. The other undermines any defence that might be offered for those mores and institutions. The result is an explosive mixture of moral indignation and moral relativism or scepticism.

Barzun continued “We should not be misled by the clamour and the wailing. It is our success that has caused it.” (Barzun 1954, 17) An example of success was the marked narrowing of the differential between white and Afro American wages through the 1940s and the 1950s, before legislation for affirmative action. But a degree of success was not enough for the coercive utopians and they discovered the power of discovering social crises, even if the situation was improving, such as teenage pregnancy, poverty and the murder rate in the 1950s (Sowell 1988).

Sowell's international study of affirmative action described the gap between the rhetoric and the reality of preference policies and the pattern of events which he found around the world. Generally the demand for preferential policies came from well educated, 'new class' members of supposedly disadvantaged groups. The same people also become the main beneficiaries of preference policies which tend to further disadvantage the majority of their brethren. This was demonstrated in Malaysia where the gap between rich and poor Malays widened in the wake of preference policies for ethnic Malays (Sowell 1990, 49).

Culture and Freedom

After his work on race Barzun turned to the cultural roots of democracy. Written on the eve of World War Two On Human Freedom (1939) was a tract for the times. The author addressed the temper and tone of mind that is required to achieve peace, prosperity and especially freedom while moderating the obsession with politics. “Salvation by Political Action” has been described as one of the great myths of the 20th century because it has led people to expect too much from politics and to the politicisation of everything under the sun (the personal is political). Further, the idea of salvation by revolutionary political action often results in obsession with ends regardless of means to legitimate monstrous crimes for the “greater good” in future.

Barzun challenged a number of prejudices which confuse the conception of democracy. “The first of these prejudices is to believe that our choice is a political one when it is, as a matter of sober fact, cultural. We think that we can deal with matters that involve our life and liberty by acting as partisans, whereas the very thing we want can only be achieved by acting as artisans. I mean by this, taking and rejecting [policies and plans] in the light of purpose, regardless of groups, labels and the mock scrimmage of politics.” (Barzun 1939, 6)

He explained his point with the example of progressive education where, as a participant in the public debate he was often confronted with demands to declare his position. He pointed out that Progressive Education is a label for a collection of practices, some of which are absurd and some are admirable. “Why anyone should relinquish his sacred right of criticism and blind his judgement of concrete particulars by either endorsing or rejecting the abstract ‘whole’ would be inexplicable, were it not for the presence of the political-minded among us”. (ibid, 7)

The next major instalments in his project were Darwin, Marx and Wagner: Critique of a Heritage (1941) and Romanticism and the Modern Ego, first printed in 1943 and reprinted in 1961 as Classic, Romantic and Modern. The nomination of Wagner rather than Freud in the trinity of emblematic modern minds is a sign of Barzun's profound interest in music and the arts. He argued that these men achieved their reputations by catching the spirit of the age, like surfers on a wave, backed by the formidable public relations exercises mounted by their followers. This earned them the status of intellectual icons despite their lack of originality and the significant flaws in their systems. He described in some detail how all the leading ideas of evolutionary theory, socialism and the leading role of the artist were commonplace for decades before the big three started work.

Barzun was especially critical of the way that their adherents promoted determinism and scientism, with truly disastrous political consequences in the twentieth century. This runs parallel with Hayek’s critique of “constructivist rationalism” whereby utopian social reformers feel obliged to recreate society in the shape of their dreams. In addition to the shortcomings of their systems, two of the three titans were monstrously egocentric and unprincipled exploiters of their friends and denigrators of their enemies. These personal characteristics became prominent in the modus operandi of their followers.

Education and the “house of intellect”

In 1943-44 Barzun spent his sabbatical leave on a study tour to “take the temperature” of education across the nation. “Under every meridian on this continent I have been privileged to attend meetings of the curriculum committee which was, it seemed, sitting continuously from coast to coast; and I had learned enough about finance, faculty clubs and state and campus politics to equip a dozen administrators” (Barzun 1981, xxv). The result was Teacher in America, first published in 1945 and reprinted in 1981, a tour de force of the challenges and difficulties in the education system such as the notion that learning has to be “fun”, various misguided fads promoted in Teacher Training Schools and the soul-destroying drudgery of the PhD “octopus”.

The Preface of the 1981 edition is a mournful reflection on several decades of regression in the public education system, much of it driven by the graduates of the courses in Education which he deplored in the first edition. “Thirty-five years have passed, true; but the normal drift of things will not account for the great chasm. The once proud and efficient public-school system of the United States, especially its unique free high school for all—has turned into a wasteland where violence and vice share the time with ignorance and idleness, besides serving as battleground for vested interests, social, political, and economic.” (Barzun 1981, ix). He described the decline as “heartbreakingly sad” and he suggested that this occurred with the very best intentions to expand the scope of the schools with a wave of additional responsibilities and progressive innovations to promote personal development, citizenship and sociability.

Good teachers are cramped or stymied in their efforts, while the public pays more and more for less and less. The failure to be sober in action and purpose; to do well what can actually be done, has turned a scene of fruitful activity into a spectacle of defeat, shame, and despair.

The new product of that debased system, the functional illiterate, is numbered in millions, while various forms of deceit have become accented as inevitable—”social promotion” or for those who fail the “minimum competency” test; and most lately, “bilingual education,” by which the rudiments are supposedly taught in over ninety languages other than English. The old plan and purpose of teaching the young what they truly need to know survives only in the private sector, itself hard-pressed and shrinking in size. (ibid, x)

His comments on the universities were equally pungent, informed by his heavy involvement in administration at the highest level and the material which he collected for The American University (1968) which is treated below.

In The House of Intellect (1959) he explored the influences that distract so many intelligent and educated people from clear, direct and analytical thinking. He pointed out that intellectuals themselves have been the major agents in the erosion of the life of the mind along with the influence of distorted views of Science, and the unhelpful contribution of Business inspired by misplaced Philanthropy.

He described some of the problems which flowed from the well-meaning efforts of foundations and corporations to ameliorate the human condition by funding university-based research and the international exchange of ideas. He noted the impact on departmental budgets when foundations gave short-term grants with inadequate allowance for overheads and the beneficiaries expected to be kept on in perpetuity. Much effort was diverted from serious long-term projects into preparing grant applications to attract funding for "exciting and relevant research" and preparing papers (similarly exciting and relevant) for international conferences.

At another level of analysis of the “house of intellect” Barzun paid attention to the mostly informal “house rules” which influence the way we organize ourselves for learning and scholarship and the way we exchange ideas and opinions in conversation. Addressing the craft of intellectual work he wrote On Writing, Editing and Publishing (1971), Simple and Direct: A Rhetoric for Writers (1975) and The Modern Researcher (2003). He explained that he was talking about the cultivation of “intellect” rather than intelligence or creativity because little can be done about the supply of native talent but a great deal can be done to maximise the productivity of our intellectual efforts. This calls for appropriate habits and disciplines ranging from effective note-taking in the lecture theatre and the library to efficient management of citations and references when writing for publication.

Among the house rules are the rituals of conversation in all its various modes from the encounter at the elevator or the bus stop to the dinner table, the cocktail party and the academic conference. Barzun referred to Tocqueville’s remarks on the lack of freedom in American democracy which Toqueville attributed to pervasive pressure for conformity which he encountered in the 19th century (Barzun 1939, 34). This pressure undermines the capacity for civil disagreement on controversial matters. Barzun deplored the awkwardness which he saw emerging in social contexts when there was a threat of “highbrow” talk or mention of “hot” topics. One of the consequences is the family tradition of “no religion or politics at the dining table”. Barzun wrote before the modern times when formal house rules on conversation have appeared in the form of laws and codes related to “hate speech”, trigger warnings and the demand for safe spaces where only approved ideas may be expressed. Unlike the kind of practices and procedures which Barzun advocated to free up the flow of conversation and facilitate the nuanced consideration of divisive issues these rules are designed to avoid issues and restrict free speech.

In Science: The Glorious Entertainment (1963), Barzun catalogued and criticised many conflicting and incoherent perceptions of science that are abroad in the land, some of them exerting a malicious influence on the humanities and many of them either trivialising or sensationalising the activities of scientists. In this book be built on the case that he sketched previously in the first 1945 edition of Teacher in America ”If science students leave college thinking, as they usually do, that science offers a full, accurate, and literal description of man and Nature…if they think theories spring from facts and that scientific authority at any time is infallible… and if they think that science steadily and automatically makes for a better world – then they have wasted their time in the science lecture room and they are a plain menace to the society they live in” (Barzun 1981, 129-30).

In 1968 he published his account of the tendencies in American higher education as the rapid post-war expansion of universities and colleges strained to breaking point the traditions and disciplines which nurture learning and scholarship. As if to underline his concerns The American University appeared in the year that students around the world started setting fire to their campuses, including his own. He considered that the distraction of the Vietnam war and the threat of the draft were the last straws added to a raft of legitimate student grievances regarding the erosion of teaching by academics whose loyalties were progressively drawn away from the students and the faculty. He described the “flight from teaching” which started during the New Deal when the administration began to recruit academics in numbers. At first the rotations were short term and positions were only held for one or two years but that condition was relaxed during the war. After the war the universities and colleges expanded rapidly and at the same time they took on a growing list of “social responsibilities” aided by the foundation funding described above. This lured staff into “exciting and relevant” work outside the classrooms. “This new behavior forced on the academy could be called a species of colonialism on the part of the foundations and the government. Bringing money, they obtained areas of influence and exerted control without rights; their favor was sought and cherished; and they obviously diverted the professorial allegiance from the university to the outside power. With a dispersed, revolving faculty, the institution ceased to have a recognizable individual face…the university lost its wholeness (not to say its integrity) and prepared the way for its own debacle in 1965—68.” (Barzun 1981 xii)

Further waves of government regulation and supervision in favor of women and minorities drove the colleges and universities to employ additional regiments of administrators and the days are beyond living memory when a university could be run by a Bursar and a handful of clerical staff while the faculties looked after themselves. Barzun provided representative statistics from the 1960s. “Of 25,000 souls and up: officers of instruction and research, 4,500: students 18,000: clerical, technical and janitorial, 1,800: administration, 780 (Barzun 1993, 97n).

Other factors complicated the situation. The mushrooming growth of the sector recruited many young people with no family tradition of higher education and too many of these who were bright and eager for learning found that their mentors regarded teaching as a disagreeable chore. Too many of the faculty were absent on foundation-funded excursions to address “problems of Appalachian poverty or Venezuelan finance”. Scholarship like any other craft is best learned by an apprentice working at the elbow of the master but with ballooning class sizes there were nowhere near enough scholarly elbows to go around, even at the postgraduate level. The Great Books program which Barzun and Lionel Trilling conducted at Columbia was an outstanding exception where two scholars of international stature worked through the books one by one in small face to face seminars. On the bright side, Barzun paid tribute to those who did provide excellent teaching to appreciative students.

Credentialing was becoming an issue for more occupations and professions. As degrees became common additional degrees and especially doctorates became the new minimal requirement for academics and researchers. “For most students…the shift has been from study to qualifying – a new form of initiation congenial equally to the university and to the world, for the world has allowed itself to be academized in all but its manual work” (ibid, 229). With that pressure bearing upon them students were not impressed when teachers took leave in mid-semester or left the campus entirely for a better offer elsewhere, missed office hours and generally showed their lack of interest in the chores of teaching. “These last two objects of resentment [Vietnam and the draft] were bound to fill the student mind when their mentors were so loudly diagnosing and dosing the ills of society. As for the hatred of high bourgeois culture, it was communicated by nearly every contemporary novel, play, painting, or artist’s biography that found a place in the popular part of the curriculum. So the age was past when ‘freshman year’ in a good college came as a revelation of wonders undreamed of, as the first mature interplay of minds.” (Barzun 1981, xiv)

And so the unresisted protestors took over the campuses, set fires, convened angry meetings and occupied building. Some years later Alan Bloom in The Closing of the American Mind documented some of the chaos at Cornell where he was an eyewitness to disgraceful episodes as agitators introduced firearms to the campus, intimidated staff and mobilized the race card as an additional combustible in the mix. Strangely he did not refer to Barzun’s earlier studies.

Barzun wrote “The violent rebels against boredom and neglect, make-believe and the hunt for credentials never made clear their best reasons, nor did they bring the university back to its senses; the uprising did not abate specialism or restore competence and respect to teaching” (ibid, xv). The fires were extinguished but the damage to the morale of the faculty and the integrity of the administration was not restored. The adversarial spirit shifted from physical confrontation to wrangling over rules and regulations in committees and “representative bodies” created to reconcile divergent needs and claims. As he put it “Students, faculties, and administrators tried to rebuild in their own special interest the institution they had wrecked cooperatively.” (ibid, xvi)

Music and the Arts

Barzun’s first wife was a violinist and his passion for music is apparent throughout his work. Volumes specifically devoted to music include the magisterial two-volume biography Berlioz and the Romantic Century (1950), Sidelights on Opera at Glimmerglass (2001) and two collections which he compiled - Pleasures of Music: a Reader's Choice of Great Writing About Music and Musicians From Cellini to Bernard Shaw (1951) and Music in American Life (1956). His Berlioz book ran to several editions and also appeared in a condensed form for popular consumption. A chapter in Teacher in America contemplated the balancing act required to introduce both performance and appreciation of music and the other arts, especially for students who come without a broad exposure to music at home.

Another arm of Barzun’s cultural project was to sort out the positive and negative elements in modern art. He had a head start with his early exposure to some of the practitioners before 1914 and his positive statement is in a collection of papers titled The Energies of Art (1956). This is a defence of certain types of revolutionary practices with genuine artistic merits which were not fully appreciated due to the distraction created by others who set out to deliberately affront the sensibilities of the general public as if this established a prima facie case for significance and originality. He claimed that the generation of artists who were in their prime during the period 1900 to 1914 were laying the foundations for major advances in art, transcending the schools of classicism, romanticism, naturalism and symbolism that held the stage during the previous two centuries.

There was this new surge of creation, inventiveness, new techniques, which gave promise that the 20th century would be one of the great productive periods of Western culture. It all collapsed into the tensions of the First World War. There were hundreds of thousands of gifted people killed. They were part of a break; they made a chasm. The generation that came to literary and other activities in the Twenties were very young men who did not have their elders' guidance and lacked a sense of resistance to their elders, both of which are necessary to true literary creation. (Gathman 2010)

Instead of consolidating the pre-1914 advances he argued that the arts suffered from a number of debilitating ideas which he catalogued in The Use and Abuse of Art (1974). He examined the rise of art as a substitute for religion in the nineteenth century so art simultaneously became the "ultimate critic of life and the moral censor of society". The next phase in that development was Estheticism and Abolitionism during the period 1890 to 1914 when “the tradition of the New” turned artists against past art as a point of reference for any moral or aesthetic standards. "By making extreme moral and esthetic demands in the harsh way of shock and insult, art unsettles the self and destroys confidence and spontaneity in individual conduct." (Barzun 1974, 73).This has helped to undermine the assumptions that the state and civilized society are valuable or admirable, thus impairing the effectiveness of political and social institutions and proving the destroyers' own case. By linking the growing interest and respect for art in modern times with the “dominance of bourgeoise values” Art turned on art itself by becoming a vehicle for every kind of assault on traditional standards of beauty, morality and commonsense.

That was written forty years ago and since then increasing numbers of students have been exposed to even more advanced "theory" to justify the assault of Art on our senses and sensibilities. In the fourth lecture he moved on to another piece in the crazy pavement of modern art, the function of art as redeemer, linked with the concept of art as a substitute for religion. Barzun accepted the common ground, that the power exerted by great art on receptive persons is a religious power, and he pursued the consequences that can follow when that kind of influence is not checked by critical thinking and a sense of history. Finally he discussed the individual and collective forms of salvation through Art that have been promulgated for 200 years. By “collective salvation” he meant the appeal of revolutionary art which offers the artist a special role, first as evangelist and later as beneficiary, in the utopian society brought about by the revolution.

His legacy

As Barzun passed his centenary he could look back on a body of scholarly work and commentary which few people could equal but he must have been disenchanted by the widespread neglect of his efforts. Perhaps he suffered instead of gaining by the expansion of the universities. William W. Bartley, in his posthumous collection of writings on scholarship and the universities Unfathomed Knowledge, Unmeasured Wealth (1990) propagated the counterintuitive idea that the expansion of the universities, more especially the dissemination of examinable knowledge, represents a threat to the growth of knowledge and even to literacy itself. (Bartley1990, 194). Such a view would have been regarded as ludicrous when three per cent of people went to universities, as it was in Australia at the start of the 1960s but nowadays with more than 30% on campus and some talk of 60% it looks more plausible.

No doubt Barzun challenged some academic empires. Also, like some other original and independent scholars such as Edmund Wilson and R. G. Collingwood, he did not establish a significant school or following. He had many admirers but there did not appear to be anything like a Barzun circle or school to systematically perpetuate his ideas and his influence. This is apparent in the collection of papers in his honour, From Parnassus (1976) which is disappointing in the very ordinary quality of the contributions. Moreover the biographical piece by Lionel Trilling is practically useless because the author fell ill and died leaving little more than rough notes. This is most unfortunate because Trilling, as a longtime colleague and friend off campus, might have shed some light on little-known aspects of his life such as the unbuttoned man in his domestic setting, and some insights into the demons and aspirations which drove him to read and write so much.

What is to be done?

The paper started with a call for economists to be alert to cultural and moral issues in view of the role of the moral framework among the pillars of classical liberalism. What are economists and public policy analysts supposed to do? The most obvious thing is to be aware of the good scholarly work on the synergy of markets and morals that is going forward and to support the groups and organizations which are fighting the battle “on the ground”. These include The New Criterion, Accuracy in Academia, Intellectual Takeout, The Diverse Academy and The American Scholar to name a few.

Cultural conservatives have usually been engaged in the “culture wars” but in modern times they have not always been strong in support of the market order, as described in Hayek’s Why I am not a conservative (Hayek 1962, Postscript). An outstanding exception was the late Michael Novak (1933-2017) who contributed a stream of books and articles on the power and the virtues of democratic capitalism. That line of work is ongoing with scholars such as Samuel Gregg and his colleagues at the Acton Institute, the Journal of Market & Morals and the Institute for Studies of Religion at The University of Texas (Baylor). There are signs that this is becoming an academic growth area, perhaps encouraged by Douglas North’s later work which took his studies of institutions beyond politics and the law to culture and social norms (Nye 2016). Other substantial works in the field include Reckoning with Markets: Moral Reflections in Economics (Halteman and Noell 2012), a major contribution by Gaus (2011), What Adam Smith Knew: Moral Lessons on Capitalism from its Greatest Champions and its Fiercest Critics (Ottterson 2014a) and The End of Socialism (Otterson 2014b).

Turning to the partnership between political economists and cultural conservatives, what is a policy wonk who reads The Independent Review to make of Barzun’s opus? Surely there is something in his portfolio, perhaps the House of Intellect, or Teacher in America to throw into the suitcase with the latest edition of The Journal of Economic Methodology when packing for the summer vacation.

REFERENCES

Bartley, William W. 1990. Unfathomed Knowledge, Unmeasured Wealth: Universities and the Wealth of Nations. La Sale, Illinois: Open Court.

Barzun, Jacques. 1932 The French Race: Theories of Its Origins and Their Social and Political Implications. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press.

Barzun, Jacques. 1937. Revised 1965. Race: a Study in Modern Superstition. New York: Harper & Row.

Barzun, Jacques. 1939. Of Human Freedom. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Barzun, Jacques. 1941. Darwin, Marx, Wagner: Critique of a Heritage. London: Secker & Warburg.

Barzun, Jacques. 1943. Romanticism and the Modern Ego. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Barzun, Jacques. 1945. Reprinted 1981. Teacher in America. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund. The 1981 Preface http://www.the-rathouse.com/JacquesBarzunPreface.html

Barzun, Jacques. 1950. Berlioz and the Romantic Century. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Barzun, Jacques. 1951. Pleasures of Music: A Reader's Choice of Great Writing About Music and Musicians From Cellini to Bernard Shaw. New York: Viking Press.

Barzun, Jacques. 1954. God's Country and Mine: A Declaration of Love, Spiced with a Few Harsh Words. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Barzun, Jacques. 1956. Music in American Life. Blooomington: Indiana University Press.

Barzun, Jacques. 1956. The Energies of Art: Studies of Authors, Classic and Modern. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Barzun, J. 1959. The House of Intellect. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Barzun, Jacques. 1964. Science: The Glorious Entertainment. London: Secker & Warburg.

Barzun, Jacques. 1968. Reprinted 1993. The American University: How It Runs, Where It Is Going. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Barzun, Jacques. 1971. On Writing, Editing, and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barzun, Jacques. 1974. The Use and Abuse of Art. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Barzun, Jacques. 1975. Simple and Direct: A Rhetoric for Writers. New York: Harper & Row.

Barzun, Jacques. 2000. From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, 1500 to the Present. Boston: Harper.

Bloom, Allan. 1987. The Closing of the American Mind: How higher education has failed democracy and impoverished the souls of today’s students. New York: Penguin.

Gathman, Roger. 2000. The Man Who Knew Too Much: Jacques Barzun, Idea Man, The Austin Chronicle, Friday October 13. https://www.austinchronicle.com/books/2000-10-13/78886/

Gauss, G. 2011. The Order of Public Reason: A Theory of Reason in a Diverse and Bounded World. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Halteman, J. and Noell, E. 2012. Reckoning with Markets: Moral Reflections in Economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hayek, Friedrich A. 1960. The Constitution of Liberty. London: Routledge.

Kimball, Roger. 2000. Barzun on the West. The New Criterion 18(10) June: 5-11.

Lovejoy, Arthur O. 1949. Communism versus Academic Freedom. The American Scholar 18 (3). 332-337.

Nye, J. V. C. 2016. “Douglas C. North: The Restless Innovator”. The Independent Review, 21, no. 1: 133-137.

Otteson , James R. (Ed.) 2014a. What Adam Smith Knew: Moral Lessons on Capitalism from its Greatest Champions and Fiercest Opponents. New York: Encounter Books.

Otteson, James R. 2014b. The End of Socialism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sowell Thomas.1988. Endangered Freedoms. CIS Occasional Papers 22. The Fourth John Bonython Lecture. Sydney: Centre for Independent Studies.

Sowell, Thomas. 1990. Preferential Policies: An International Perspective. New York: William Morrow and Company.