Is the proposal for a constitutionally entrenched Voice to parliament and the executive government “progressive”? If so, in what sense? This will seem to most people a no-brainer. After all, nowadays, in one of the great acts of linguistic appropriation of our time, “progressive” has come to be seen as virtually synonymous with left-wing.

And what could be more left-wing than the Voice, endorsed as it is by just about all the left-of-centre forces in Australian politics, including all factions in the Labor Party, right through to the most wild-eyed Trotskyist sect.

After all, so goes the argument, it is just a modest step toward securing recognition, justice and recompense to the most oppressed part of the Australian population.

Only a racist, or a member of the far-right could be against it, surely? We hear this claim repeatedly by people who call for a calm, civil, “conversation”, sometimes as a precursor to launching into a vicious ad hominem attack on Voice opponents.

This near unanimity is surprising, given that the Voice involves inserting a permanent, racially discriminatory provision in the Australian constitution, that confers on one racially defined section of the community an additional means to influence legislation and decisions that affect everybody, not just aboriginal people.

Especially, given that it contravenes the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1965, and entering into force in 1969. Article 1 defines racial discrimination as:

... any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

There is provision for “special measures” to overcome disadvantage, but these must be temporary, intended to disappear once their objectives have been achieved.

This has been the preponderant view on the US Supreme Court since 2003, when Justice Sandra Day O’Connor cast the key vote preserving affirmative action but suggested a 25-year timeframe to allow the achievement of the measure’s goals. This ruling figured in the debate leading up to the Court’s most recent decisions rejecting race-conscious admissions at Harvard and the University of North Carolina.

However, if adopted, the Voice will be for keeps, permanently cemented into the Australian constitution. “Progressive” opinion is not just comfortable about this, but absolutely insistent on it.

Some defenders of the Voice, such as Sky News presenter Chris Kenny, deny that it has anything to do with race, but is about aboriginal descent. This is a distinction without a difference—notice that the words of the Convention cited above prohibit distinctions based on “race, colour, descent”, all terms denoting what people have mind when talking about race and racism.

So, how can a racially discriminatory provision possibly be progressive?

To make sense of this, it is necessary to take account of the extraordinary transformation in the Left’s attitude to race and racism that has occurred in the decades since the Convention was adopted in the 1960s.

The language of the Convention reflects the universalism with regard to race that was then central to the progressive worldview, the most famous expression of which was Martin Luther King’s great civil rights speech in 1963 in which he looked forward to the day when his children would be judged by the content of their character, not the colour of their skin.

Back then, leftists (not just leftists, of course) looked forward to a colourblind future, one in which racial identity would become increasingly irrelevant. The old Left view was that it is both irrational and morally repugnant to judge anyone by the melanin content of their skin, or any other heritable surface feature. The idea that racial identity would define a person’s essence was anathema.

An interesting aspect of this was that the aboriginal groups that initiated calls leading to the 1967 referendum were divided about whether to modify or eliminate all references to race in the Constitution.

The upshot of these discussions was that they decided to preserve the racial power in Section 51 that allowed the Commonwealth government to make specific laws “for any race”, while removing the specific exclusion of aborigines. Moreover Section 25, which envisaged race-specific disqualifications from voting, was also preserved.

Why not eliminate all references to race in the Constitution? Apparently aboriginal advocates were talked out of this by white advisers on the basis that any future laws were likely to be beneficial to them, an early portent of the abandonment of racial universality.

Since then, with the highly regrettable embrace by the Left of the politics of culture and identity, the “progressive” attitude to race has changed beyond recognition. This is largely a result of the work of the academic theorists who concocted Critical Race Theory (CRT) and its odious sub-discipline Whiteness Studies, that treats “whiteness” as a kind of pathology. These theories originated in the US but have spread throughout the Western world.

Instead of colour-blindness, CRT practitioners—and they do see it as a practice, or praxis, undergirding political activism—demand a hyper-awareness of racial identity, and how this supposedly determines each person’s status as either a bearer of racial privilege (“white people”), or as one of the oppressed (“people of colour”).

Here is one particularly weird aspect of today’s “progressive” thinking about race.

You may have heard of the one drop rule, a term widely used in the American South during the Jim Crow era for the idea that having one drop of Negro blood was sufficient to define a person as black, and subject to all the racially discriminatory laws and attitudes of the period, including the prohibition on miscegenation, sexual relations between whites and “coloured” people. The Nazis had a similar attitude—to be admitted to the Nazi party, candidates had to prove using baptismal records the absence of any Jewish ancestor since 1750.

Today, with the rise of identity politics, the one drop rule is back. Recall how Senator Elizabeth Warren claimed native-American status on the strength of her “high Cherokee cheekbones” and some very distant ancestry, which DNA analysis put at between 1/32nd and 1/1,024 of her genetic heritage. Ridiculous, but it was enough to for her check the native-American box to help her academic career.

Nowadays, it is common for Australians to claim aboriginal heritage on equally spurious grounds. And, woe betide any “white” person who questions any of this, such person being likely to face to accusations of racism, or as in the case of television presenter Andrew Bolt, brought before a court. It is also taboo to state the obvious truth that someone of mixed racial background is, well, a person of mixed racial background.

The “indigenous” author Bruce Pascoe has taken this a step further, failing to refute claims that all his grandparents were English. Pascoe has done very well out of his claimed indigeneity, producing an acclaimed, but nonsensical, book about pre-colonial aboriginal agriculture.

Melbourne university has even made Pascoe a Professor in Indigenous Agriculture on the strength of it! It seems there is a lot to be gained by claiming membership of an “oppressed” identity these days.

Instead of an insistence on strict racial equality, today’s “progressives” call for differential treatment grounded in this privileged/oppressed binary. Talk of colour-blindness serves to distract from this understanding, and so is deemed racist. Hence, we find universities like the University of California, drawing up lists of taboo words and phrases, including “when I look at you, I don’t see colour”.

At American universities, racially segregated spaces, dormitories, graduation ceremonies, clubs and societies, are making a comeback at the behest of “progressive” administrators, academics and activist students, as well as calls for “race-based” political mobilizations.

Instead of consistent opposition to all racial vilification, there is the legitimization of derogatory statements directed at “white people”, and of character traits exemplifying “whiteness”, which includes having a strong work ethic, punctuality and a commitment to seeking objective truths, an oxymoron in the eyes of postmodern academia.

And cultivation of racial awareness is too important a progressive priority to be left to the later stages of the education/indoctrination process. In the US, Britain, and Australia, we see programs to cultivate heightened racial awareness being brought in at the primary school level, a development celebrated in a two-part documentary by (who else?) our ABC.

This documentary, titled The School that Tried to End Racism, describes a program being implemented in a NSW public primary school modelled on similar programs in the US and UK. The children are prompted to identify and think deeply about their racial status, and then required to participate in a game where they take starting positions in a race that reflect their status in the pecking order of privilege or oppression.

Some of the children (10-12 years old), especially those clearly white, were obviously distressed by this process—but, hey, this is a small price to pay to achieve the noble progressive goal of heightened racial awareness.

After all, the white children need to recognize they are the bearers of a kind of racial original sin. This, under the auspices of a “conservative” state government—pity an old-school leftist wasn’t in charge!

Do you think this is an exaggeration? Let’s go to the authority on all things progressive, in the Australian context anyway, the ABC. There was an episode of a Radio National program called The Minefield, devoted to exploring wicked social problems and ethical dilemmas with the strange title Wrong to be White that featured two academic commentators on racial issues, moderated by the person who runs the ABC’s religion and ethics website, Scott Stephens.

The discussants made clear that, in their view, there was indeed something gravely wrong with being white. According to Stephens (41 minutes in):

The great moral debility about being white is that people have wilfully chosen the trinkets and accoutrements of the accretions of power and privilege over a much more fundamental bondedness with other human beings … I mean that is, if we were speaking in a theological register, we would call that a tremendous and even radical sin.

So, according to Scott Stephens, “being white” is a “tremendous or even radical sin”. Astonishing stuff. It inverts the old racist notion, used to justify slavery, that black skin was the Mark of Cain. Instead of aiming for a world where there are no moral hierarchies based on race, the CRT brigade want an inverted hierarchy. And they call this anti-racism?

How do the race theorists and their followers think this will advance the cause of “reconciliation”? The American scholar Karen Stenner has documented how denunciation of people based on group identity especially if deemed unfair, can be seen as a “normative threat” leading to the very opposite of what reconciliation advocates claim to want.

So much for the “progressive” attitude to race. So, how does this racist ideological poison bear on the Voice debate?

To get a sense of this, it is useful to bear in mind that, if the referendum is successful, the Voice will be just the first stage in a three-step process to achieve reconciliation and social justice outlined in the Uluru Statement from the Heart (TUSH), adopted at a gathering of aboriginal people and organisations in 2017. Prime Minister Albanese has declared his government’s full commitment to all stages set out in TUSH.

The two subsequent steps will be negotiations to achieve a treaty (Makarrata) between the Australian state and aboriginal Australia, seen as a separate sovereign entity, this to be followed by a process of “truth telling” that will describe in detail the manifold ways in which indigenous people have been oppressed and dispossessed since British colonization. The end point is expected to be a demand for substantial reparations as partial compensation for this litany of harms.

Don’t hold your breath waiting for any concession that Western civilization might have brought significant benefits to aboriginal people—modern technology, including medicine, the rule of law, the very civil liberties that have allowed aboriginal people to redress historic wrongs and take advantage of democratic political processes.

It would be interesting to hear prominent aboriginal identities in media, academia and politics like Stan Grant, Marcia Langton and Noel Pearson trying to imagine what their lives would be like had there been no colonization (a pure thought experiment, since Australia would undoubtedly have been colonized by another European state).

No, on this view, colonization has been an unalloyed negative. The flip side is the presumption that pre-colonial life in Australia was wonderful, an Edenic paradise untouched by the pathologies of domination, oppression, violence and war introduced by the British colonizers. Societies in which the various tribes sprung from the earth in possession of just those lands that were their due, without coercion or conquest, a state of near-perfect social justice, this happy state of affairs brought to an abrupt end when Arthur Phillip’s First Fleet arrived at Sydney Cove.

Here is the thing about “truth telling”. According to the epistemology of postmodern academia that underpins the theories of the academic race ideologues, there are no ascertainable objective truths.

Truth is held to be perspectival, and plural, with different “truths” available depending on each person’s standpoint, based identity or a combination of identities. For a “white” person to assert something to be objectively true is in reality just an exercise of power designed to perpetuate existing relations of domination and oppression.

These notions are succinctly explained in a short video by Professor Juanita Sherwood, Academic Director of the National Centre for Cultural Competence at the University of Sydney, in which she stresses the importance of “knowing that there is not only one way of knowing, being and doing, but there are many, and that they are all valid”. Sydney University has announced that these notions of cultural competence are to be incorporated in all their curricula, across the board.

The scientific method, developed by “white people”, is just one among many, ways of knowing. Other ways are equally, if not more, valid and must be respected, and certainly not denied. Hence, an article about aboriginal habitation of Australia on the national Museum of Australia’s website, mentions sophisticated dating methods to determine when they arrived, but goes on to respectfully refer to aboriginal views of creation that hold they have been here since land was created, the Dreaming. Things have gone further in New Zealand, where Māori mythology (“ways of knowing”) are being accorded equal weight to modern science in science classes.

So, it is not surprising that the identarian race theorists posit indigenous culture as the polar opposite of oppressive “white” civilization. Consider this, from a lengthy article on identity politics written by a strong academic advocate of it, that appears on the website of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Indigenous governance systems embody distinctive political values, radically different from those of the mainstream. Western notions of domination (human and natural) are noticeably absent; in their place we find harmony, autonomy, and respect. We have a responsibility to recover, understand, and preserve these values, not only because they represent a unique contribution to the history of ideas, but because renewal of respect for traditional values is the only lasting solution to the political, economic, and social problems that beset our people.

Notions of domination noticeably absent, all harmony, autonomy and respect? What is this based on? Could it be based on careful empirical studies of indigenous societies? How can that be squared with overwhelming evidence of widespread tribal warfare before European colonization, as well as unrestrained violence against aboriginal women reported by early British and French explorers of Australia?

What about the claim that “renewal of respect for traditional values” is the only solution to the problems that beset indigenous societies. What studies of the efficacy of actual implemented policies is this based on?

As it happens, Australia provides a test case for this hypothesis. What happens when ideological fantasy becomes the premise of policy? The impact of the change in indigenous policy since the revolution brought about since the late 1960s under the influence of former Reserve Bank chairman H.C. Coombs provides a tragic case study.

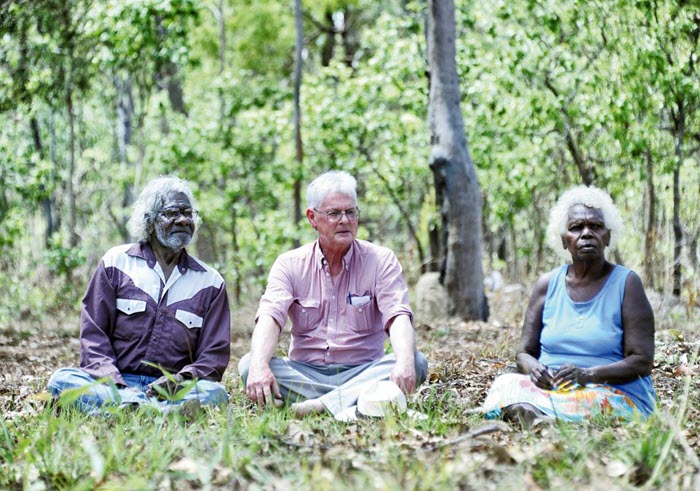

I had not realized the magnitude of this disaster until I read Peter Sutton’s book The Politics of Suffering, published in 2009. This is an extraordinarily important book that did not receive anything like the attention it deserved when published.

Sutton has had a close association with indigenous communities extending over thirty years. He was a key advocate and researcher supporting the aboriginal position in some of the most important native title cases. No-one can challenge Sutton’s bona fides as a committed friend of the aboriginal people and advocate of their causes, and as an outstanding scholar of aboriginal culture.

The book paints an horrific picture of what has happened over the past few decades. It describes how communities that forty years ago were poor but liveable have become disaster zones of violent conflict, rape, child and elder assault, with what he terms Fourth World health conditions.

Sutton is extremely distressed and angry about this, and derisive of the use of anodyne terms like “aboriginal disadvantage”, preferring to talk of the “levels of sheer suffering” of indigenous people today.

That this should have happened despite one well-intentioned policy initiative after another, the granting of land rights, the setting up of autonomous aboriginal governance and service delivery structures, and the spending of tens of billions of dollars annually on both mainstream and indigenous-specific programs, is especially perplexing.

Sutton argues that the deterioration has occurred not despite the policy shift but was in large part caused by it. His argument is complex and subtle but can be summed up by what he terms the Coombsian contradiction - a policy framework:

Built on a willingness to publicly ignore the profound incompatibility between modernisation and cultural traditionalism in a situation where tradition was, originally at least, as far from modernisation as it was possible to be.

Here is what Sutton has to say about the relationship between violence and traditional culture:

My unqualified position is that a number of the serious problems indigenous people face in Australia today arise from a complex joining together of recent, that is post-conquest, historical factors of external impact, with a substantial number of ancient, pre-existent social and cultural factors that have continued, transformed or intact, into the lives of people living today. The main way these factors are continued is through child-rearing. This issue is particularly important, and controversial, in the area of violent conflict.

Sutton refers to a blanket of silence “promoted and policed by the Left and a number of indigenous activists” that has constrained honest debate on these matters from the 1970s until relatively recently.

Sutton was an academic anthropologist and linguist—and an important truth teller. However, he was easy for the mainstream media and academia, and government, to ignore.

More recently, we have seen the emergence of a number of high-profile indigenous truth tellers, whose testimony should be much harder to ignore, people like Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, Warren Mundine, and Anthony Dillon, people with the background to shed important light one what goes on in traditional aboriginal communities, all of whom have expressed strong opposition to the Voice.

Of these, Price has achieved most prominence, having been elected to the Senate from the Northern Territory in 2022, and currently serving as opposition Shadow Minister for Indigenous Affairs. Her mother Bess is a full-blooded aborigine, who for a time served as a minister in the Northern Territory government. Before becoming a Senator, Price was the Deputy Mayor of Alice Springs.

If any people have the “lived experience” to comment on the role of traditional culture in indigenous communities, it is Bess and Jacinta Price, both of whom grew up in central Australian tribal communities and have given impressive testimony about the problem of endemic violence in them – aboriginal women in the NT are thirty-five times as likely to be hospitalized by violence as women in the general population.

Jacinta has been speaking and agitating about this problem, and its cultural roots, for years, and has been constantly exasperated by the lack of support and sheer disinterest from “progressives”.

In a presentation to the National Press Club in 2016, she opened with this:

Traditional culture is shrouded in secrecy, which allows perpetrators to control their victims. Culture is used as a tool by perpetrators as a defence of their violent crimes, or as an excuse or reason to perpetrate. It is not acceptable that any human being have their rights violated, denied and utterly disregarded in the name of culture.

She elaborated on this theme in a speech, Homeland Truths: The Unspoken Epidemic of Violence in Aboriginal Communities, delivered in the same year:

Growing up in and knowing my culture, I know that it is a culture that accepts violence and, in many ways, desensitizes those living the culture of violence.

Referring to a cultural practice that could potentially result in the killing of aboriginal women, she notes:

The public reaction was deathly silence… there was no reaction from the hypocrites in our southern cities. No complaint from anybody: no human rights lawyer, no feminist, no activist, no one made it into the media with a word of concern that women could be executed in the Northern Territory for even accidentally walking on to a ceremonial ground.

Now, that is some powerful truth telling. So, how was that received by the great and the good of “progressive” politics? By Price’s account, all she and her mother received from that sector was vituperation and abuse, up to and including actual death threats, a pattern that has continued up to the present day with Noel Pearson’s extraordinary ad hominem attack on her in a recent radio interview.

You see, by insisting on telling these truths, rather than reciting the ideology-soaked fantasies of the postmodern race ideologues, she was committing a grave heresy, an act of treachery against her own identity. Postmodern academia has coined a sinister new epithet to describe people like Price: Native Informant.

The concern of Price and her colleagues and supporters is that the Voice, and what is intended to follow, the Voice > Treaty > Truth Telling, sequence will, far from enabling meaningful improvements in the lives of aboriginal people, perpetuate the disastrous policies informed by the fantasy version of indigenous culture that has predominated in recent years.

One thing that has changed in recent decades is the emergence of a university educated aboriginal elite, most of whom are committed to a policy paradigm grounded in an idealized version of aboriginal culture that has yielded such disappointing results over the past forty years. It has been a dismal failure, with very little to show by way of closing the gap between indigenous people and the general population, despite a succession of well-intentioned initiatives costing tens of billions of dollars every year.

Price fears that if the Voice is established, it is likely to be quickly captured by this elite, and they will perpetuate the tried-and-failed policies that she, Sutton and others have been so critical of. What will ensure the success of the Voice, compared to a succession of earlier initiatives to address aboriginal disadvantage?

I was a member of federal parliament when the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) was set up in the late 1980s. Reading the 1987 speech outlining the proposal with the ambitious title Foundations for the Future by the then Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Gerry Hand makes the Voice seem like déjà vu all over again.

It’s all there! The speech is replete with well-intentioned sentiments and high hopes: talk of recognition, broad-based representative structures, indigenous input into programs, indeed actual control of them, the need for a treaty, a Makarrata process.

Well, not all. The key distinction between the Voice and ATSIC is the proposed constitutional entrenchment of the former. It was possible to legislatively abolish ATSIC, which indeed happened in 2005 with bipartisan support after ATSIC was consumed by allegations of corrupt and incompetent program administration, and criminality on the part of senior figures, including Chair Geoff Clark. Well before this, ATSIC’s failings at program delivery were all too apparent. In 1995 it was stripped of responsibility for administering aboriginal health programs, in response to a flood of demands from local aboriginal health providers.

Voice advocates tout constitutional entrenchment as a key advantage of the Voice compared to ATSIC. An advantage for who? Not, apparently, the disadvantaged communities that desperately need honest and competent program administration.

The pseudo-progressive race ideologues insist that we are defined by our manifold identities, and that if we are the holders of an “oppressed” identity, we must fully embrace the corresponding culture, irrespective of its cruelties and other defects.

In a number of recent cases, aboriginal children removed from birth parents due to neglect, malnourishment and extreme family violence and happily settled with white foster parents have been subject to repeated separation from their foster parents, in the face of vehement objections from the children themselves, motivated by a futile quest for non-existent suitable kinship care options to keep them in touch with their culture.

As a result, according to Jacinta Price, bureaucrats are “putting kids in the hands of abusers”, prompting her to demand a Royal Commission to thoroughly investigate the sexual abuse of indigenous children. Yet “progressive” politicians and commentators are still in denial about these terrible circumstances.

So, what is truly progressive? To insist on some sanitized, idealized understanding of indigenous culture, to base policies on this flimsy foundation, and to persist with this course in the face of overwhelming evidence that it harms the very people the ideologues claim to advocate for? And to vilify any genuine truth tellers as Native Informants, race and identity traitors?

Or, to face realities honestly, to adjust policy accordingly, with the overriding goal of improving the life chances of some of the most impoverished and severely disadvantaged people in the country?

As to culture, Jacinta Price in a speech made back in 2016, spoke eloquently against the culture-as-prison mentality favoured by the identarian race ideologues:

Why is it that we should remain stifled and live by 40,000-year-old laws when the rest of the world has had the privilege of evolution within their cultures, so that they may survive in a modern world?

That is the genuinely progressive view, if the word means anything at all.