I used to enjoy the science fiction series StarTrek—before, that is, it went woke in the past decade. One of the main antagonists was an alien species known as The Borg, a vast cybernetic hive mind that overwhelms and co-opts other alien species and absorbs them—and their technologies—into the hive. The Borg’s signature threat was “resistance is futile”, its stated goal to “achieve perfection”.

In the previous two articles (here and here) I argued that the CCP regime in China aims to utilize the most powerful tools of modern technology to create a perfect totalitarian state, harnessing artificial intelligence (AI) to resolve the weak point in Orwell’s 1984 dystopia—who gets to monitor the huge volume of data collected by all the telescreens.

The CCP Borg has already absorbed the previously relatively free society of Hong Kong. Next on the menu is the Taiwan, which stands as a stark refutation of the racist notion that Chinese people value basic freedoms less than Westerners. This would have major geostrategic implications, especially given that island's dominance of global manufacturing of the most sophisticated semiconductor devices.

The possibility of technology-powered global totalitarianism appears in all the compendia of existential risks we could face in the present century that I cited in the earlier articles, but it is generally treated as an abstract and distant prospect, often tied to the emergence of artificial general, or human-like, intelligence.

I have made the case that this is far too complacent. The aspiration for a perfect form of “algorithmic governance” is being brought into being as we speak within the borders of China and, as the sources I cited make clear, the regime clearly aspires to extend its scope globally.

This should figure far more prominently in our consideration of the spectrum of existential risks, both because it is an appalling prospect in its own right, but because, as the current pandemic illustrates, a secretive totalitarian regime can delay awareness and action on other grave dangers.

The naivete of western governments, institutions—especially universities—and media and scientific figures has given added impetus to this danger. Not least because, as the British/American historian Niall Ferguson has observed, the monofocal obsession with climate change has “crowded out” thinking about this (and other) dangers, as has the “woke” ideology that sees little that is worthwhile in the liberal civilization we inherited.

But there is a further point. As I argue below, the CCP’s “dual circulation” vision of a restructured global economy would tie the outside world to it in a relationship of growing but asymmetrical dependency. How does the West’s planned shift to renewables to address climate change sit with this plan? Could it facilitate the rise of the hegemon?

Way back in the early 1990s the former Prime Minister Paul Keating made an amusing addition to Australian vernacular English when he said, in a debate about the importance of structural economic reform, that “I guarantee if you walk into any pet shop in Australia, the resident galah will be talking about microeconomic policy”.

Nowadays the proverbial galahs (a species of cockatoo, for anyone who is wondering) never stop chattering about “existential risk”, or more specifically, one putative source of such risk—climate change.

In making this observation, I am not disputing that climate change is an important issue that requires a substantive response, but as the British/American historian Niall Ferguson argues in his new book Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe it is one of a number of such risks that face us in the present century, very serious risks consideration of which has tended to be overshadowed by the all-pervasive climate change debate.

I think Ferguson has a point. It is a well confirmed observation about people’s weighing of relative risks that disproportionate attention is given to risks that that have the greatest apparent public salience, those with the most visibility in the media.

That is why, in the two previous articles in this set, I have stressed the range of dangerous possibilities we could face in coming decades, both from nature and human technological innovations, some potentially much more lethal than climate change—and some even genuinely existential in that they threaten our survival as a species.

The key thing about existential risk is that, once invoked in a debate, it acts as a kind of trump card (if sufferers from TDS will pardon the pun). After all, what could be more important than a risk that is existential? President Joe Biden recites it regularly as part-justification for the massive, and highly dubious, economic agenda he is trying to foist on the American public funded by money creation on an unprecedented scale.

The child-prophet Greta Thunberg can invoke it with a burning passion, chiding all who might demur for their “childish fantasies about endless economic growth”, to the fawning adulation of the great-and-the-good, and just about all of the Western media. She is young—she cares about the future—not like you old fogies devoid of any stake in the long-term future. Or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortes, who warned a couple of years ago that we only have twelve years to save the earth.

So, drop everything else and focus on the most drastic measures to address climate change. Our survival as a species, the earth itself, depends on it.

In think this is a serious mistake. In the quote from Niall Ferguson I cited above he went on to note that in January 2020, when the galahs at the Davos World Economic Forum were chattering about climate change (with a leavening of discussion about social justice and its important sub-discipline “climate justice”), the Covid-19 pandemic was undergoing the early stages of its global spread.

Plague flights left Wuhan for the four corners of the earth as China sealed its internal borders to internal travel from Wuhan and, as we now know, it was already on the loose in Italy and parts of the United States in December 2019. At that stage, nobody knew how serious – even potentially existential – the threat from this virus would turn out to be.

Almost certainly, this is not the last threat from pandemics, including biological experiments gone wrong – or even gone right, in the case of bio-weapons research of the kind the CCP has almost certainly been conducting despite it being a signatory to the Biological Weapons Convention.

In a recent article, Australian investigative reporter Sharri Markson cites an acknowledgement in the Chinese submission to the 2011 review of the Biological Weapons Convention that such experiments could pose a “threat to mankind” (this was scrubbed from its submission to the next five-yearly review in 2016).

In a detailed analysis of the CCP regime’s biological warfare activities, the Israeli researcher Danny Shohan notes its clever exploitation of dual-use research to mask its biological warfare activities and enlist Western expertise:

One major factor utilized by China within that context is ‘dual-use’ biotechnological and biomedical disciplines. Sophisticatedly vague at times, and at times in a recognizable manner, the various concerned Chinese systems, sub-systems and facilities apply dual-use biotechnological and biomedical disciplines that pertain to both conventional or defensive essentials, but are BW oriented.

Another major element is the prevalent presentation of the concerned Chinese facilities as being ostensibly civilian, or belonging to ostensibly civilian entities. This conduct has further advantage in that it supports the formation of international, fruitful interfaces with technological suppliers and with top scientific institutions abroad. The practice of that conduct is often assisted by Chinese scientists who are situated for a long time, or permanently, at various foreign universities and scientific institutes, particularly in the US.

These observations (made in 2015) are highly relevant to what we now know about the compromised role of Western universities (which trained most the Chinese researchers) and scientists who participated in and even helped secure US government funding of the incredibly dangerous gain-of-function research being carried out at the Wuhan Institute of Virology that I described in detail in the previous article in this series.

As I pointed out in the previous article, both Lancet and Nature magazines, or their parent organisations, were beneficiaries of funding from the CCP regime, and both these esteemed publications played a key role in the early discrediting of the lab-leak theory of the pandemic’s origins, suppressing articles from highly qualified scientists arguing the contrary.

The significance of this is hard to overstate. We have become used to hypocritical corporate chiefs and media figures, desperate to access the huge Chinese market, bending over backward to avoid offending the CCP regime. But the compromising of the most influential scientific journals in the world, previously thought to be of unimpeachable integrity, takes matters to a whole new level.

Which brings me back to the main theme of the earlier articles—the risk that in the coming decades the CCP regime, as its relative economic and technological advantage rises, will emerge as the world’s preeminent power.

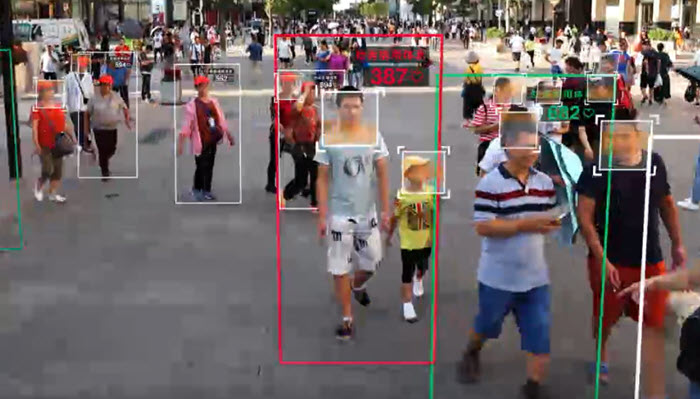

This is a regime that has already within its own borders implemented new technologies to establish a system of surveillance and control without historical parallel—indeed beyond the dystopian nightmare of George Orwell in 1984.

A regime that, already, is bent on extending its power beyond its borders to the wider world, and able to bend democratic governments to its will and mute or silence opposition to its gross human rights abuses, such as we see with the Uighurs in Xinjiang, the largest mass incarceration of an ethno-religious minority since the fall of the Third Reich. Check out the truly pathetic, anodyne reference to this in the communique of the G7 summit in Cornwall, and the abject of even Muslim states like Turkey to seriously take up the Uighur cause.

We have already seen the subjugation of Hong Kong, and the extinguishment of its freedoms. Next on the menu is Taiwan, an issue with crucial geostrategic as well as human rights implications given that island's dominance in the manufacturing of the most sophisticated semiconductor chips. According to the Wall Street Journal:

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co ’s chips are everywhere, though most consumers don’t know it. The company makes almost all of the world’s most sophisticated chips, and many of the simpler ones, too. They’re in billions of products with built-in electronics, including iPhones, personal computers and cars—all without any obvious sign they came from TSMC, which does the manufacturing for better-known companies that design them, like Apple Inc. and Qualcomm Inc. QCOM 1.26%

TSMC has emerged over the past several years as the world’s most important semiconductor company, with enormous influence over the global economy. With a market cap of around $550 billion, it ranks as the world’s 11th most valuable company.

The CCP regime’s ability to shape or influence discourse in the democracies is already clear, but will grow in significance with the comprehensive digitization of all forms of communication, making them especially vulnerable to cyber operations.

Could we be seeing the rise of a global totalitarian hegemon?

This possibility appears in some form in all of the compendia of existential risks emanating from the researchers and cross-disciplinary centres I mentioned in the earlier articles. However it is always couched in unspecific terms, a distant possibility, often linked to the emergence of “strong” AI, or Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), the human-like ability to conceptualize general problems, not the domain-specific abilities of the current generation of AI.

The development of AGI will certainly take things to a whole new level, a real “hinge point” in the development (or extinction) of our species. But well before this point AI solves the key weakness in Orwell’s depiction of universal surveillance in 1984—who will monitor the vast mass of data. AI, tied to technologies like facial recognition and pattern recognition, provides a non-human solution to this problem, enabling the entire citizenry of a country to be monitored for signs of nascent dissent, and to be “denied the ability to move” if detected.

This is an issue that is encroaching on us now. Yet, in many discussions and debates about emerging threats to democratic governance, it hardly figures, such discussions tending to stress the threats from “populism” or “white supremacy”. In a recent IQ2 debate about Orwell’s legacy two names figured prominently: Putin and Trump, with not a single mention of the CCP regime. In a recent book by the influential historian and Atlantic magazine columnist Anne Applebaum The Twilight of Democracy, an authority on autocratic regimes in central and eastern Europe, the CCP scarcely rates a mention.

A brand new book, Atlas of AI, by the highly credentialed author Kate Crawford (a senior principal researcher at Microsoft), specifically on the political implications of AI focussed on how AI leads to resource depletion and labour exploitation, but nothing about the prospect of totalitarian “algorithmic governance” by the CCP. The only oblique reference dismisses such concerns as “a paranoid vision of defending a national cloud against the racialized enemy” (p. 187).

The CCP regime is the elephant in the room, looking us in the eye, that many fail, or refuse, to see. The most insightful exceptions to this include some tech entrepreneurs, acutely aware of the technological possibilities. In an interview just published Marc Andreessen, who developed the first internet browser, put it this way:

On the other hand, China has a strategic agenda to achieve economic, military, and political hegemony by dominating dozens of critical technology sectors -- this isn't a secret, or a conspiracy theory; they say it out loud. Recently the tip of their spear has been networking, in the form of their national champion Huawei, but they clearly plan to apply the same playbook into artificial intelligence, drones, self-driving cars, biotech, quantum computing, digital money, and etc. Many countries need to consider very carefully whether they want to run on China Inc.'s technology stack with all of the downstream control implications. Do you really want China to be able to turn off your money?

Now, roll the tape forward and try to imagine the kind of world subsequent generations could be living in.

So what has any of this to do with climate change? How could climate policies, most importantly those of the United States, vitiate efforts to prevent the rise of a global totalitarian hegemon? If these goals conflict, how to strike an appropriate balance? How can climate policies be adjusted to minimize this problem?

To address these matters we need to consider some additional features of the CCP’s plan to reshape the world order.

Start with how the CCP perceives its economic relationship with the rest of the world developing in coming years, and the key concept they call “dual circulation”, described in an important article by Mark Leonard on the Project Syndicate website in March of this year:

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s new strategy centers on the concept of “dual circulation.” Behind the technical-sounding phrase lies an idea that could change the global economic order. Instead of operating as a single economy that is linked to the world through trade and investment, China is fashioning itself into a bifurcated economy. One realm (“external circulation”) will remain in contact with the rest of the world, but it will gradually be overshadowed by another one (“internal circulation”) that will cultivate domestic demand, capital, and ideas … In doing so, China will also seek to make other countries more dependent on it, thereby converting its external economic links into global political power.

In a nutshell, the CCP aspires to a global economic order characterized by minimal Chinese dependence on the outside world, but maximized dependence by the outside world on it.

The central imperative driving the CCP’s priorities is to expand its global clout to the point where, according to the same article:

Today’s main geopolitical contest is not just about enforcing global rules; it is about who makes them. Whereas the West previously struggled to secure Chinese compliance with the trade, investment, and intellectual property (IP) frameworks it had crafted, China is now also seeking to make and enforce the rules.

This includes becoming the dominant force in international institutions that bear on the dissemination of information, like the International Telecommunication Union, the UN body responsible for “facilitating international connectivity” and developing “the technical standards that ensure networks and technologies seamlessly interconnect”, which is currently chaired by a Chinese national.

Another important aspect of the CCP approach to economic development is the doctrine of “civil/military fusion” that mandates that all research carried out in China be shared with the People’s Liberation Army. It is described in this article by Lorand Laskai that appears on the website of the Council on Foreign Relations:

Since Xi Jinping ascended to power in 2012, civil-military fusion has been part of nearly every major strategic initiative, including Made in China 2025 and Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Plan. The goal is to bolster the country’s innovation system for dual-use technologies in various key industries like aviation, aerospace, automation, and information technology through "integrated development".

This confirms the naivete of Dr Fauci and others in the West who seem happy with assurances that no military use would be made of research they collaborated with, or helped to fund, in the Wuhan lab would or could be applied to military purposes. In 2017 Google opened an artificial-intelligence laboratory in Beijing.

The reality is that in China every commercial and research organisation is legally obligated to co-operate with the PLA if called on to do so.

Bear in mind that China, along with Russia, is embarked on a massive program to expand and modernize its military capabilities, fully leveraging the regime’s industrial, scientific and technological assets. The US, by contrast, has announced a real cut in defence expenditures in its current budget proposal with part of the remainder devoted to activities related to climate change, as many of its key weapons system age.

So how will the CCP’s bid to become the global hegemon be detained by the global climate change policy agenda? Not much, in the short term anyway. According to a Yale research publication that came out last March with the self-explanatory title Despite Pledges to Cut Emissions, China Goes on a Coal Spree:

A total of 247 gigawatts of coal power is now in planning or development, nearly six times Germany’s entire coal-fired capacity. China has also proposed additional new coal plants that, if built, would generate 73.5 gigawatts of power, more than five times the 13.9 gigawatts proposed in the rest of the world combined. Last year, Chinese provinces granted construction approval to 47 gigawatts of coal power projects, more than three times the capacity permitted in 2019.

China has pledged that its emissions will peak around 2030, but that high-water mark would still mean that the country is generating huge quantities CO2 — 12.9 billion to 14.7 billion tons of carbon dioxide annually for the next decade, or as much as 15 percent per year above 2015 levels, according to a Climate Action Tracker analysis.

So, for now, it is full steam ahead for the Chinese economy, unconstrained by concerns about climate change which, together with large scale fossil fuel production and consumption by India, Russia, Indonesia, Vietnam and Japan (over 600 new coal-fired plants in the pipeline) vitiates earnest efforts by the Western powers to “move the needle” on future the future path of the earth’s temperature.

Then there is this irony: For now, the West is overwhelmingly dependant on China for production of solar cells, wind turbines and other items necessary for the renewables transition, highly likely made with inputs produced by slave labour, according to an article in Politico Europe:

“Everybody knows what’s going on in China, and when facilities are based there you have to accept that there’s a high possibility that forced labor will be used,” said Milan Nitzschke, president of EU ProSun, an alliance of solar businesses seeking to promote sustainable, solar manufacturing based in the EU.

“Nearly every silicon-based solar module — at least 95 percent of the market — is likely to have some Xinjiang silicon in,” said Jenny Chase, head of solar analysis at Bloomberg”

Could this production be brought back onshore to the US, Europe or other friendly powers? It would be hard, given China’s propensity to massively subsidise any strategically important industry, according to industry analysts.

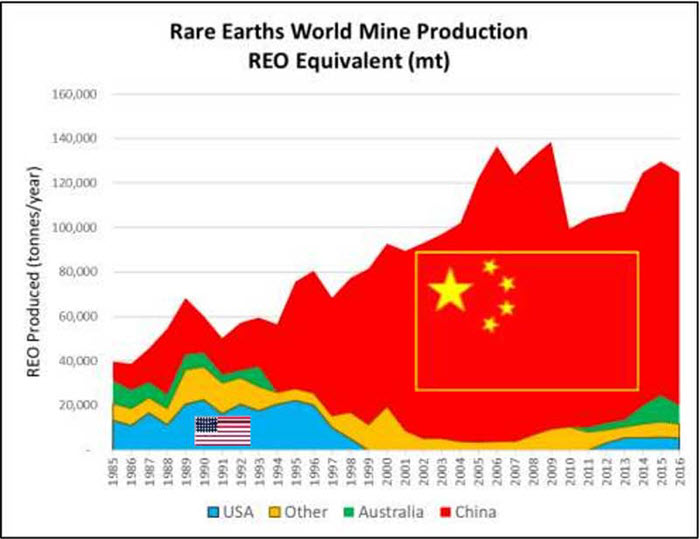

It gets even better, from the CCP’s point of view, when account is taken of Chinese dominance of production of “energy transition minerals” (ETMs) necessary to produce the wind, solar and battery items the renewable energy transition will require.

According to a report by the International Energy Agency (which is committed to the renewables transition) The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions the demand for minerals such as lithium, graphite, nickel and rare-earth metals would explode, rising by 4,200%, 2,500%, 1,900% and 700%, respectively, by 2040. These are massive increases, and the production capacity doesn’t exist at present, and will take considerable time to develop.

Here is another problem. In the just released book Atlas of AI the author Kate Crawford notes that China supplies 95 percent of the world’s rare earth minerals, but that their dominance:

… owes far less to geology than to the country’s willingness to take on the environmental damage of extraction. Although rare earth minerals like neodymium and cerium are relatively common, making them usable requires the hazardous process of dissolving them in large volumes of sulfuric and nitric acid. These acid baths yield reservoirs of poisonous waste that fill the dead lake in Baotou. This is just one of the places that are brimming with what environmental studies scholar Myra Hird calls “the waste we want to forget.”

Try selling that to Western woke elites!

To sum up, a massive and rapid switch to renewables starting in the next decade would be likely to take the US from a state of energy independence to one of dependence on China for the means to keep the lights on and industries running, as the Chinese economy roars ahead using all available energy sources without let or hindrance.

Add to that the impact on the US economy of the considerable expenditures needed to make this transition, and all the other social priorities of the administration, largely funded by money creation on an unprecedented scale. As some, including former Obama Treasury Secretary Larry Summers have noted, this is a seriously risky undertaking.

What will be the long term effect of the huge debt burden being incurred, and the danger of reawakening of inflation? In a recent editorial the Wall Street Journal noted that the President’s own fiscal 2022 budget projections indicate two years of strong growth due to the “sugar hit” of all the spending followed by a decade of sub-two percent growth—the return of “secular stagflation”, with little prospect of a major revival of American manufacturing.

Not a great prospect for the democracies, but a wonderful step toward the CCP ambition of a “dual circuit” global economy with it very much in the driving seat.

CONCLUSION

In this set of three articles I have discussed the broad spectrum of “existential risks” that we could have to deal with in coming decades, while noting that public discourse has overwhelmingly tended to focus on one—climate change—effectively crowding out adequate consideration of other dangerous possibilities, some of which are truly “existential” in the sense of threatening our survival as a species.

I have stressed one source of such risk, in particular, that in the decades to come we could see the emergence of a global totalitarian order, with the catastrophic reduction in freedom and loss of human potential that this would entail.

Such a possibility is mentioned in all of the compendia of existential risks that I referred to, but generally as an abstract, distant possibility, often tied to what could happen if some state (or non-state) actor were to gain a decisive lead in the development of artificial intelligence.

I contended that, far from being distant, we see this scenario being brought to fruition right now in CCP-controlled China, with the full harnessing of all that new technologies offer to create a pervasive system whereby actions—even thoughts—that the regime approves of are rewarded and those that it does not punished. The CCP aspires to a system in which, using sophisticated pattern recognition, facial recognition and other technologies potential dissent can be detected and suppressed in its nascent stages.

So, why focus on this? For two reasons.

Firstly, and most obviously, it is an appalling possibility in and of itself. Who would want to live in such a “Borg like” world, probably divided between a ruling caste and the oppressed and despised constrained in a digital panopticon, like the Uighurs today.

Secondly, because in a world dominated by a totalitarian hegemon, how could we ensure that due consideration is given to other serious dangers? We have already seen that prospect exemplified with the Covid-19 pandemic, as courageous Chinese whistle-blowers have disappeared, died in mysterious circumstances, or forced to flee the country.

This suppression, and Western naivete in accepting the CCP’s goodwill, ensured the early spread of the virus around the world, leading to millions of avoidable deaths. The CCP was able to harness global organisations like the WHO to give support to its lies, and was even able to enlist foreign scientists and prestigious journals like The Lancet and Nature to its purposes.

In recent years, the CCP has acquired a new skill—keying in to the ideological predilections of Western “progressives” to achieve its goals. Again, the Covid-19 pandemic is illustrative, as leftists denounced as “racist” or “xenophobic” the early border closures, even in some cases supporting the lies about the virus’ limited transmissibility, such as Nancy Pelosi calling on her constituents to “crowd into” Chinatown on the Lunar New Year 2020, at a time we now know the virus was silently spreading.

There is wide agreement among those who study existential risk that, with the emergence of a range of new technological possibilities, the main sources of such risk are now likely to be human-created rather than natural in origin, things like out-of-control biotechnology, including experiments that mess with the human genome, nanotechnology and dangerous physics experiments, as well as the older worry about nuclear weapons.

It is essential that, at a global level, we are able to hold open and honest debates about the these dangers, and how they can be mitigated, before we go too far down the track with any of them. In some cases, research in specific areas may need to be prohibited.

The problem is, of what value are all the earnest ethical discussions at the specialist centres at Cambridge and Oxford universities, MIT, and others, if a secretive regime driven by a desire for global dominance goes its own way? There are reports that the CCP regime is conducting military-oriented research on ethnically-selective viruses, for example.

Then there is artificial intelligence, which Vladimir Putin, among others, has picked as the master technology of the 21st century, allowing whoever captures a decisive lead to do all sorts of things—including devising ways to achieve a nuclear first-strike capability--and rule the world. The CCP aspires to achieve a clear lead in AI and related technologies, such as quantum computation, by 2030.

That is before we get to the possible development of what researchers term Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), the transcending of the domain-specific capabilities of current AI to the ability to “ understand or learn any intellectual task that a human being can”.

The prospect of AGI seems in the realm of science fiction, and even the possibility of it is strongly contested by some specialists and philosophers, but a poll of researchers in the field put the median estimate of when it could happen with 50 percent probability between 2040 and 2050 (with 16 percent thinking it would never happen). Bill Gates, among many others with tech backgrounds, is seriously worried about it.

But it does not stop there. Once AGI is achieved, there is the prospect that a self-conscious machine could create future generations of itself with improved abilities, which could then in turn improve on itself, and so on recursively. The result, some say, would be an intelligence explosion.

Some scholars argue that this prospect means that we are moving into a period of exceptional significance for the future development of our species, a hinge point that will determine the future of humanity into the distant future.

How to avoid such a development being severely adverse to humanity? We need to consider this, even if it is judged that the more extreme possibilities described above are deemed remote. Like a large asteroid strike, this is a possibility that is genuinely existential—and if the above estimates of when it could arrive are right, it is a problem that could unfold on more or less the same timescale as dangerous climate change.

There is some serious debate going on about this. For a sample check out these video presentations by physicist Max Tegmark, neuroscientist Sam Harris, and pioneering computer scientist Stuart Russell.

One thing they agree on that, for there to be any chance of a benign outcome, the issue has to be addressed before AGI emerges. There needs to be “fail safe” systems to ensure such an intelligence does not—cannot—act against human interests and human values. Would the CCP co-operate in such an endeavour? Maybe. But maybe it would prioritize maximising the military capacity such a technology could offer, and developers of military technologies tend not to be too fastidious about human life.

The emergence of the CCP regime as an unchallengeable global hegemon in the decades to come would be a real catastrophe, as disturbing in its own ways as the more pessimistic projections of unrestrained climate change.

ISSUES ARISING

I would be interested your views on a number matters that arise from this article (or any other thoughts you might have):

For example, you may think that I have deprecated the importance of climate change by drawing attention to the range of other catastrophic risks facing humanity in the present century.

Indeed, you might want to contend that climate change really is the existential risk, the only one that threatens our very existence, or the viability of human civilization, and that talk of other dangers is a distraction.

...Or you might take the opposite view, arguing that the obsession with climate change is inflated, at most a manageable problem that will unfold gradually.

…Or you might say that the prospective the rise of a global totalitarian hegemon is just not an existential risk, maybe a distinctly unpleasant prospect, to be sure, but not in the same league as climate change.

…Or you might think I have grossly overstated the danger of the CCP regime becoming a totalitarian hegemon. Maybe you think such worries are grossly overstated, a manifestation of xenophobia—fear of “the other”, and we should be more concerned with fixing our own societies, remedying their multiple defects and denials of social justice

And in any case if there is a genuine conflict between policies to address these two dire possibilities, how could such a conflict be resolved in a way that prioritizes appropriately and does justice to both?

I look forward to getting your opinions on the above matters—or anything else you might want to say—and will respond to all constructive contributions whether supportive or opposed.

If you want to say I am completely wrong-headed, that is fine, but please give reasons and let's try and keep it civil. With that, we will hopefully start to develop some interesting discussion threads that clarify the main points of disagreement.