In this essay I will argue that identity politics as a philosophical concept can and does promote real freedom of speech by striking the right balance between positive and negative freedom. Also, I argue that this is done by appealing to the values of negative freedom of speech put forward by J.S Mill, and that group identities do hold privileged knowledge that can only be obtained by providing its members with a platform.

Introduction and defining identity politics

Attempting to come to a strict definition of identity politics can be quite difficult, since many apply it in different ways and the term has gained so much public attention its detractors will be tempted to interpret it in its least charitable way. For instance, the Stanford Encyclopaedia of philosophy says:

The phrase ‘identity politics’ is also something of a philosophical punching-bag for a variety of critics. Often challenges fail to make sufficiently clear their object of critique, using ‘identity politics’ as a blanket description that invokes a range of tacit political failings’.

The Stanford article, however does offer a broad description, which will suit our purposes here, and that description is:

The laden phrase ‘identity politics’ has come to signify a wide range of political activity and theorizing founded in the shared experiences of injustice of members of certain social groups. Rather than organizing solely around belief systems, programmatic manifestos, or party affiliation, identity political formations typically aim to secure the political freedom of a specific constituency marginalized within its larger context. Members of that constituency assert or reclaim ways of understanding their distinctiveness that challenge dominant oppressive characterizations, with the goal of greater self-determination.

In this essay I will argue that applying a specific kind of identity politics, which is the seeking out specific people on the basis of their identity groups in media and academia, promotes what I call ‘real’ freedom of speech. I will do this by demonstrating that this promotes positive freedom of speech, seeks out knowledge that can only be obtained by these identity groups, and also maximises the utility that the promotion of negative freedom of speech usually provides.

Mary’s privileged access to acquainted knowledge

Many philosophers would be aware of Frank Jackson’s ‘Mary in the black and white room’ thought experiment, where Mary, a colour scientist, lives her whole life seeing only black and white but nonetheless learns all there is to know about the colour red. Jackson asks us, when Mary finally sees the colour red, has she learned something new? Jackson originally used this thought experiment to refute physicalism. However, he conceded years later that Mary learning something new by experiencing the colour red can be consistent with physicalism by contrasting different kinds of knowledge. One such kind of knowledge is knowledge of acquaintance. Knowledge of acquaintance is knowledge derived from direct observation, whereas descriptive knowledge is knowledge derived from learning about something that has not necessarily been directly observed.

So, Mary experiencing red for herself, now knows what it is like to see the colour red. And for most of us in the world, we too know what it is like to see the colour red. However, do we know what it would have been like for Mary when she saw red for the first time? We can imagine that if we assume Mary had 20/20 vision and was not colour-blind, that she would be seeing the colour in an approximately similar way we would see it. But, we would not know how she felt when she saw red for the first time. We could imagine what that may be like, and what we imagine may be very close to the truth, but we would not thereby know what it was like. The only person who can truly know such things would be Mary. Richard Swinburne describes this kind of knowledge as privileged access. He calls this privileged access because no one can gain the required knowledge of acquaintance to truly know what it was like for Mary to see red for the first time except for Mary herself.

Prima facie acquainted knowledge possessed by identity groups

The claims I made above could be initially seen as an optimal argument for individualism as opposed to collectivism, because this would say that everyone, regardless of group identities, holds privileged access to knowledge that everyone else lacks, therefore to think in individualist terms would make more sense. However, although we cannot know exactly what itis like to be in someone else’s shoes, we can with increasing confidence imagine what it would be like by appealing to our own experiences. In the case of Mary, if I know she has 20/20 vision and is not colour-blind, I can with a high level of confidence imagine that what her eyes were seeing would be approximately similar to what my eyes would see. However, given that I have not spent my life only seeing black and white, I would have much more trouble imagining what it would be like regarding how Mary would be feeling. For example, would I find it exciting or scary? If there were another person who lived their life seeing only black and white, they could, prima facie, have a better time imagining these things. Furthermore, if there were a group of people who lived a life like Mary, this prima facie knowledge would be shared amongst such a group.

This prima facie knowledge can be applied to identity groups. I can know all there is to know about being a soldier in Afghanistan, but only soldiers who have been to Afghanistan would be able to say what it is like to be a soldier in Afghanistan. The only people who can come close to knowing this would be fellow soldiers in Afghanistan, or at least those who have been in similar circumstances. However, does this mean we have no hope at all in improving our knowledge about what it is like to be soldier in Afghanistan? Not necessarily. We can improve our capacity to imagine such situations by having them tell us.

Determinism, interactionism, and their impact on situated knowledge

At least at the macro level, we live in a deterministic world. In the philosophy of mind, the truth or falsity of determinism can be contentious issue, but whether one is a dualist, physicalist, libertarian or determinist, the vast majority would all agree that our values and desires are at least greatly determined by biology, environment, or an interaction of both. Some sociologists claim that these facts mean that our knowledge is situated, or dependent upon our social environment, leaning towards a post-modernist view of ethics and knowledge. Although I reject post-modernism, the concept of situated knowledge is not entirely without merit. Our differences, even in the most egalitarian world, would have impact on how we view the world, what we notice and do not notice and what we can imagine easily and have more difficulty imagining.

It would take an extreme optimist to claim that we live in a completely egalitarian world, so it is fair to claim that those who possess traits that are of the minority instead of the majority, the well-off instead of the not-well-off and the noticed instead of the unnoticed, that those traits will impact in a significant way their experience of the world. Understanding which groups of people are likely to have an experience of the world significantly different from our own, is essential to promoting the values of freedom of speech, which I will discuss next.

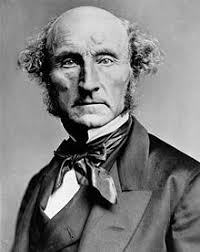

J.S Mill’s reasons for negative freedom of speech demonstrate the utility of positive freedom of speech

In J.S Mills’ On Liberty Mill makes the case of why allowing freedom of speech matters from a Utilitarian standpoint. Put roughly, his main arguments for freedom of speech can be summarised as follows:

- Not only allowing the maximum number of points of views to be expressed, but also allowing yourself to hear the maximum number of points of views expressed, brings about the strongest probability of reaching the truth.

- All sides of the argument must be heard, if one has not heard all sides of the argument, it becomes further away from truth and closer to dogma.

- By having no restrictions on speech, these two things listed above will be realised.

Mill’s interest was focussed on the state and society not interfering with people expressing themselves. Therefore, his focus is best described as the ‘negative’ aspect of freedom of speech. In contrast, ‘positive’ freedom of speech is allowing someone access and/or resources to express themselves. A simpler way of describing this would be the act of providing someone with an audience would be to promote their positive freedom of speech.

When we consider Mill’s first two claims, an argument can be made that positive speech also achieves these outcomes. If we give the maximum number of people an audience, this would assist in having the maximum number of people hearing the maximum number of points of view. Also, not only allowing someone with an opposite viewpoint the opportunity to speak, but doing our best to give them an audience, would assist in having the maximum number of people hearing all sides of the argument.

There are those who reject the distinction between positive and negative freedom or claim that the only kind of freedom that matters is negative freedom of speech. However, I argue that both sides of politics agree on the legitimacy of positive freedom of speech. A common complaint from the right is that the ABC is too left leaning, and a common complaint from the left is that Sky News, at least at night, is too right leaning. These complaints can only be made sense of by advocating positive freedom of speech, because the complaint is that a media source is only giving a platform to one side of the argument, even though they may not be interfering with the other side from speaking. Furthermore, the request at the Blackheath Philosophy Forum to limit questions to 2 minutes can also only be justified through the promotion of positive freedom of speech. In fact, it is an instance of constraining one person’s negative freedom of speech, since we have interfered with a person’s desire to continue to speak after 2 minutes, to give other people the positive freedom of speech of getting a chance at the microphone.

There are those who reject the distinction between positive and negative freedom or claim that the only kind of freedom that matters is negative freedom of speech. However, I argue that both sides of politics agree on the legitimacy of positive freedom of speech. A common complaint from the right is that the ABC is too left leaning, and a common complaint from the left is that Sky News, at least at night, is too right leaning. These complaints can only be made sense of by advocating positive freedom of speech, because the complaint is that a media source is only giving a platform to one side of the argument, even though they may not be interfering with the other side from speaking. Furthermore, the request at the Blackheath Philosophy Forum to limit questions to 2 minutes can also only be justified through the promotion of positive freedom of speech. In fact, it is an instance of constraining one person’s negative freedom of speech, since we have interfered with a person’s desire to continue to speak after 2 minutes, to give other people the positive freedom of speech of getting a chance at the microphone.

So, both negative and positive speech matter. Political philosopher Phillipe Van Parjis utilises the concepts of both negative and positive freedom in his arguments for Universal Basic Income (UBI), which he describes as ‘real’ libertarianism because it still acknowledges property rights whilst providing the safety net to allow individuals the means to live their lives as they desire. Thus, applying this approach to freedom of speech, to obtain real freedom of speech in society we need to strike the optimal balance between positive and negative freedom.

Putting it into practice: Dominant discourses and narratives

If we justify freedom of speech in J.S Mills’ terms, then we will want to have a world which has not only as many perspectives maximised as possible, but the number of people knowing these perspectives to be maximised as well. By taking a real-libertarian approach, we still acknowledge the value of non-interference against speech, but provide a platform for those who need it most. This can be done by understanding that in any society, there are dominant narratives. If we can identify the suppressed narratives, then we ought to provide those who hold those narratives enough of a platform to create a world where all narratives are well known (and of course the arguments for such narratives).

This is where identity politics can play, and I would argue has played, an effective role. The primary function of identity politics is to have groups that have shared experiences through their identity collectively coming together to make sure that their voices are heard. Obvious historical examples of this would be the unionising of the working class, the civil rights movement in the US, the first and second waves of feminism, and soon. It was the act of these people coming together due to their shared experiences based on their identity so that their voices would be heard due to their numbers, thus why protests are so effective, since they promote not only speaking, but being noticed.

In the media, there is at least a moral obligation to present all sides of a story. Consider in the United States a discussion concerning Black Lives Matter. Considering the arguments made earlier considering the value of positive freedom of speech and the acquainted knowledge possessed by African Americans who have experienced police violence, it makes sense to make an extra effort to ensure they are adequately included in the discourse. This is not to say that these views should be held with absolute authority over all other views on the matter, but if we wish to have a complete picture on the entire story, we need to be told from their perspective. This is best done by actively seeking these people out and giving them a platform.

This is not say that this understanding of identity politics is the only kind, or that it does not have limitations. There are those who would assert that these perspectives are the only views worth considering, and those of the dominant discourse ought to be silenced. This behaviour is contrary to the negative aspect of freedom of speech. However, when certain topics are raised, it is incumbent on us to consider who is included in the discourse.

Conclusion

Therefore, identity politics can promote real freedom of speech when it is used to actively seek out identity group members who are not part of the dominant discourse, and to provide a platform to them. This is consistent with the broader concept of identity politics, promotes positive freedom of speech whilst not disrupting negative freedom of speech, and maximises the utility of J.S Mill’s freedom of speech due to the information gained by their testimonies given from their acquainted knowledge.